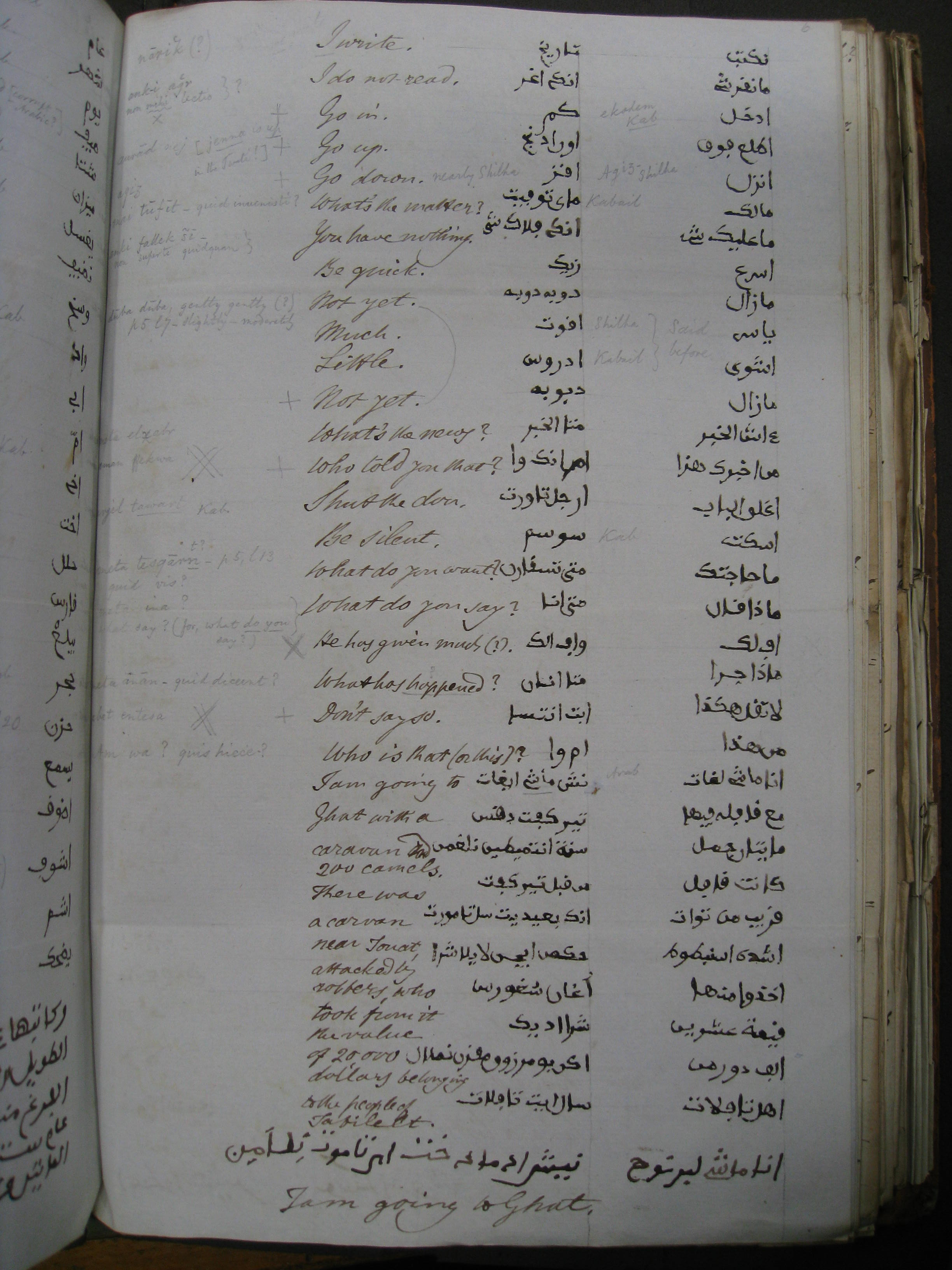

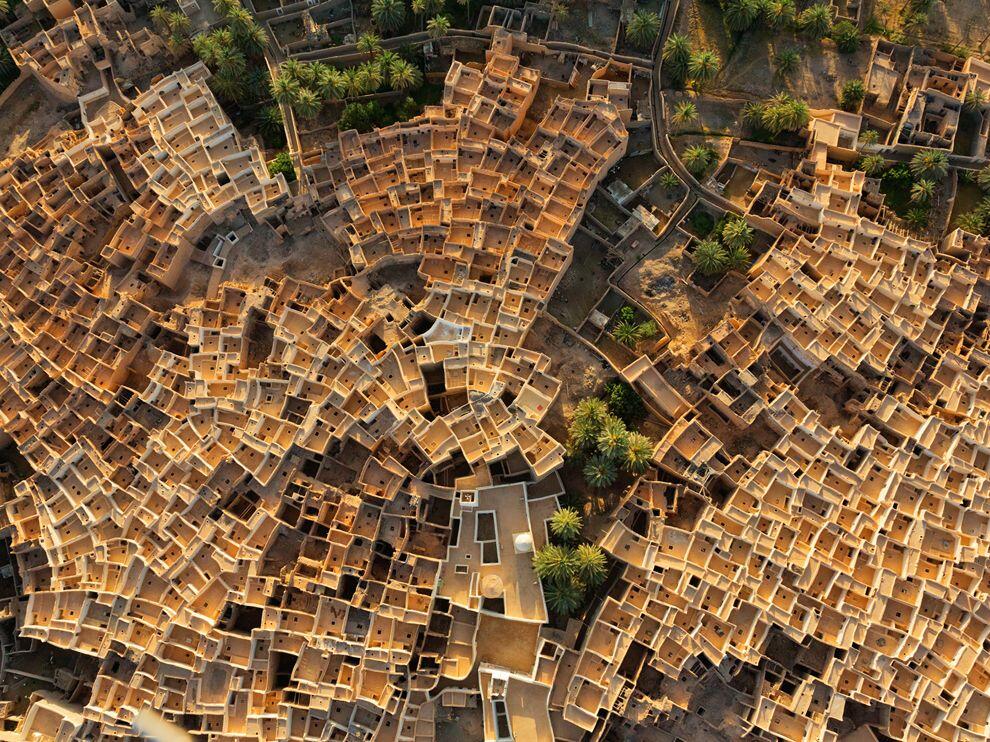

Zwaran Berber prepositions and adverbs based on T.F. Mitchell’s materials

14 October 2021 Leave a comment

[MvP: Stanly Oomen has written up yet another short part of his ongoing series on Zuaran Berber. This time he s discussing the prepositions and adverbs. Enjoy!]

In this blog I provide some notes on Zuaran Berber prepositions and adverbs. Good descriptions of prepositions in Berber are Mourigh (2016: chapter 3) for Ghomara Berber (North-West Morocco), Van Putten (2014: chapter 8) for the highly endangered Berber language Awjili (Libya). The pan-Berber proposition n has recently been given a thorough semantic and syntactic analysis in Siwi by Schiattarella (2020).

Prepositions

Prepositions occur in three forms: (a) before a noun, (b) before a pronoun, (c) independently; I haven’t yet made a table of the different forms the prepositions take in these different syntactic positions, but give a few examples of allomorphs. Nouns following prepositions are in the annexed (“construct”) state. The combination of [preposition + noun] form a prosodic unit and the accent is on the penultimate syllable and thus predictable (Mitchell 2007:20), unlike accent in the verbal domain, where it carries a distinct meaning (i.e. indicating the aorist – perfective aspectual contrast).

Berber prepositions

- l ‘to’

- i ‘for’

- g ‘in, at’

- al ‘until’

- n ‘of’

- af ‘on’ (f(ə́)ll- before a pronoun, e.g. f(ə́)ll-as ‘on him’)

- žar ‘between’ (žaráy- before a pronoun, e.g. žaráy-as ‘between him’)

- zzat ‘in front of’ (cf. zzát-ək ‘in front of you’)

- d ‘with’ (did- before a pronoun, e.g. díd-sən ‘with them’)

- s ‘with’ (sis- before a pronoun)

As for the form žaráyas: alternatively, one can analyse žaráyas ‘between him’ as žar-áyas; áyas would then be an indirect object pronoun.

Both the preposition l ‘to’ and the preposition s ‘from’ can be used to indicate the location someone is going to: the exact distribution needs further study. Compare:

fə́ṛḥat y-ṛə́wwəḥ l-tíddart

‘Ferhat went home’

idžəṃṃás ɣir y-ṛə́wwəḥ sə́-ssuq

‘one day he went to the market’ (idžəṃṃás < *idžen-n-wás ‘one-of-day (EA)’)

The preposition al ‘until’.

all-ə́gg-iḍ

‘until the evening (lit. until in the evening)’

y-əqqím s-tizzárnin al-túqzin n(ə)tta y-súggam d-ís

‘he waited for her (news) from the tizzarnin to the tuqzin prayers’

Arabic prepositions

- bla ‘without’

See the example bla ləmtiḥánat ‘without examinations’ in the example below (from a conversation):

waḷḷáhi muhu n(ə)tnin g-way(u) n-ʕamín ggayən ammídin bla ləmtiḥánat, maɣə́llik ɣə́rsən (omissible here) məlzumín gə-lmuʕə́llmin, ggáyən mən ɣir ləmtiḥánat

‘as you know, for the last two years they are taking (them) like this without examinations, because they are short of teachers (they are taking (them) without examinations) (more repetition)’

The Arabic preposition bí-‘with’ is found with an Arabic pronoun attached to it, e.g. bí-h ‘with him’, and ma bí-k ša? ‘no problems?’. It also occurs in fixed expressions, such as mbǝ́lḥǝq ‘true’ and bzáyəd ‘very, a lot’ (compare Moroccan Arabic bezzaf ‘very, a lot’). It does not occur with other nouns. A textual example:

xxúl b(ə)ʕd yumín a-y-ə́ṣbəḥ ma bí-h-š, swá swá

‘then after two days he will wake up with nothing wrong with him, perfectly well’

Adverbs

Adverbs modify propositions. A proposition can be a verb phrase, which is most often the case, or another kind of phrase. In the first example bzáyəd ‘very, a lot’ modifies y-əfṛə́ḥ ‘he was pleased, happy’, while in the second example it modifies táṣbiḥt ‘good (F:SG)’, and in the third example it modifies tamə́qqart ‘big (F:SG)’.

y-əfṛə́ḥ bzáyəd mallík y-ufa mə́mmi-s ḥált-is xír n-qə́bəl

‘he was very pleased because his son’s level (lit. condition) was better than before’

ussáni fə́ṛḥat (ə)lḥált-is d-táṣbiḥt əbzáyəd

‘Ferhat’s state (of learning) nowadays is very good’

y-igá-s(ə)n ḍḍíft d-tamə́qqart əbzáyəd

‘he put on a very large party for them (i.e. lunch at which meat in particular was served)’

The adverbs are divided in three semantic groups: temporal adverbs, place adverbs, and discourse adverbs. Most adverbs are indeclinable words and form a word class on their own. Some adverbs are nouns. Some adverbs come from original prepositional phrases. The adverb báqi ‘again, still’ is formally an Arabic active participle. Unlike in some other languages, adverbs are not derived from adjectives.

Temporal adverbs

- talží ‘in the morning’

- lwaitšá ‘the next days’

- iḍ(ə)nnáṭ ‘last night’

- íḍu ‘tonight’

- fís(ə)ʕ ‘quickly’ (<Ar.)

- díma ‘always’ (< Ar.)

- bə́kri ‘early’ (< Ar.)

- qə́bəl ‘before’ (<Ar.)

- b(ə)ʕd ‘after’ (< Ar.)

- ass lžúmʕa tálži ‘early Friday morning’

Place adverbs

- dín ‘there’

Discourse adverbs

The following discourse adverbs were found in the texts. The oaths such as b(ə)lláhi ‘for Heaven’s sake’ and waḷḷáhi ‘by God’ are placed at the beginning of a sentence. The other adverbs have more freedom of movement.

- báhi ‘okay, agreed’

- mbǝ́lḥǝq ‘true’

- bzáyəd ‘very, a lot’

- báqi ‘again, still’

- m(ə)ʕádš ‘no longer’ (frozen form < m(ə)-ʕád-š)

- xír ‘better’

- ʕad ‘still’

- b(ə)lláhi ‘for Heaven’s sake’

- waḷḷáhi ‘by God’

- báss ‘just’

- ɣír ‘only’

báhi, mbǝ́lḥǝq xir

‘agreed, it would be better, that’s true’

tadíst-iw m(ə)-ʕád-š t-tʕə́ddəm

‘my stomach no longer hurts’

t-əṃṃá-yas ‘xxúl a-n-ḥə́kkəṛ ʕad.’

‘she said to him: ‘we will see’’

y-ufa báqi zʕíma t-g(ə́)ʕməz nəttat d-yádž-is d-y-ufa zzə́r-snət (ə)lb(a)ʕḍ n-tsə́dnan yəssnínt

‘he again found Za’ima sitting with her mother and next to them were (lit. and he found next to them) a number of women he knew.’

lakən báqi w-y-nəžžə́m-š an(ə)t-y-qábəl zzat lʕílt-is

‘but he could still not meet them in the presence of (lit. in front of) his wife’

The adverb báss ‘just’ can stand at the beginning of a phrase, or at the end of it:

Before:

báss áraw wuhánit y-ətqə́l gəd-díst-iw d-y-ttḥə́rrək bzáyəd

‘(it is) just (that) this child of mine is heavy in my stomach and moves around a lot’

After:

y-əṃṃá-yas ‘(n)tš ɣsə-ɣ ak-tṛə́žži-ɣ gə-tɣúsa ídžət báss’

‘he said to him: I just have one request to make of you’

aitu ɣír baš atákzəd báss

‘this is just to make you realize’

ɣsə́ɣ-t-id á-y-ɣər báss

‘I just wanted him to study’

Sometimes, Mitchell translates báss as ‘only’.

nə́šnin n-igí g-ətməzgída n-əɣsí á-y-ɣər báss

‘we put him in the mosque only (because) we wanted him to study’

References

Mitchell, T.F. (2007) Ferhat. An Everyday Story of Berber Folk in and around Zuara (Libya). Berber Studies 17. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Mitchell, T.F. (2009) Zuaran Berber (Libya). Grammar and Texts. Berber Studies 26. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Mourigh, Khalid (2016) A Grammar of Ghomara Berber (North-West Morocco). Berber Studies 45. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.

Schiattarella, Valentina (2020) Noun modifiers and the n preposition in Siwi Berber (Egypt). In: Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 41(2): 239–263.

Van Putten, Marijn (2014) A Grammar of Awjila Berber. Based on Paradisi’s work. Berber Studies 41. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag.